Tags: America, China, COVID 19, inflation, supply chain

Category:

Investment management

“Smart people learn from everything and everyone, average people from their experiences, stupid people already have all the answers.” Socrates

I must admit that I found this a difficult newsletter to write. For much of the month, it has been hard to think of anything other than the astonishing goings-on in British politics. Further tragic distractions were provided by the shocking news of the shooting of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the extraordinary events in Columbo, Sri Lanka.

To add to the feeling of doom and uncertainty, Russian president Vladimir Putin threatened “catastrophic consequences” for global energy markets if the West impose further sanctions on Russia. If that was not bad enough, Putin ordered his generals to continue their advance into the Donetsk region of Ukraine which, sadly, will result in the deaths of yet more innocent civilians.

Matters of profit and loss pale in comparison with matters of life and death.

If 2020/21 was a ‘virus outbreak’ horror film; thus far, 2022 has been a (very) bad 1970s disaster movie. The typical opening scenario in that genre goes something like this: A problem is detected, there is a failure to recognise the gravity of the threat, which later erupts into a spectacular crisis. In the meantime, the whole situation is made much worse by the arrival of numerous new emergencies and calamities.

When one is surrounded by waves of negativity and trying to deal with the gravity of events, it is easy to miss good news. So, let me offer a few reasons for optimism that may have been easily overlooked.

Bloomberg reports that China is contemplating a direct stimulus to its economy by bringing forward $220 billion in bonds issuance to back infrastructure. You could take this as tacit confirmation that the economy is in trouble. It’s a return to the old strategy of pumping up construction spending whenever growth is running out of steam. And it’s only a matter of bringing forward spending that had already been planned.

However, the plan also shows that the authorities are prepared to relent in the face of signs that local governments are using the financing that’s there. If they’re prepared to go back to an old playbook that worked, that is a positive sign for global investors.

Plenty of bearish arguments hinge on the notion that Chinese authorities are resolved not to resort to a major priming of the pump. Any sign that they are growing less conservative is welcome. There are other unmistakable signs that China’s economic deceleration after renewed Covid shutdowns early this year hasn’t been as bad as feared. Its domestic stock market is surging back, even as the rest of the emerging world is falling.

There are reasons for this. The strong dollar is seriously problematic for other Emerging Markets but less so for China. The country’s entire experience of the pandemic is out of alignment with the rest of the world. The acute selloff for the commodities that China traditionally gobbles up, such as copper, shows the degree of concern but if the Chinese government really is prepared to pick up the pace again, that will help far beyond its own shores. It’s at least worth watching.

Inflation owes a lot, if not everything, to stretched supply chains. This problem is beyond the reach of central banks but still threatens to make the task of monetary policy far harder by embedding inflationary pressure and prompting higher wage demands.

On this issue, there is again some good news. The New York Fed now keeps an index of global supply chain pressures which brings together shipping and freight costs and other measures of how swiftly supply chains are moving. These rose sharply in 2020, declined, and then surged once more as fresh Covid-19 lockdowns affected activity, particularly in China.

The latest version of the index shows that pressure remains elevated, but is unmistakably declining:

This doesn’t mean the issue is over. It does, however, suggest that one of the world’s most acute problems is beginning to ease. Which is reason to be cheerful.

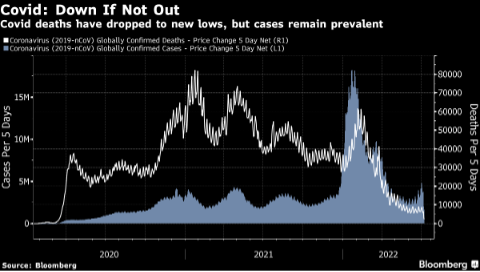

We all know from personal experience that the pandemic hasn’t gone away altogether. It is still around, grumbling away as a problem that diminishes quality of life. But at a global level, Covid 19’s ability to take lives really does appear to have been curtailed. These are the latest global numbers as reported to Johns Hopkins University. Omicron was a savage wave, but in its wake, the pandemic’s death toll has declined as never before. Nobody will say that it is over with any confidence after the false dawns of the last two years, but it is hard to see how anyone could hope for numbers much more encouraging than this, particularly after the horrors of Omicron at the turn of the year:

There is a glimmer of hope from the US that the Fed will be able to raise interest rates sufficiently to sweat inflation out of the economy without producing a painful increase in the unemployment rate resulting in a recession.

The price of copper, a bell weather because it is used in so many products is at a two-year low. Walmart, Target and other retailers are dumping excess inventories of clothing, appliances, televisions and furniture to so-called liquidators who will sell the stock to smaller stores and online sellers at knock-down prices, which will be reflected in inflation reports. Warehouses are so clogged that many retailers are telling customers to keep goods they were planning to return but with no requirement to pay!

The American economy has survived an estimated 48 recessions, predicted and actual, since the Articles of Confederation were ratified by the 13 original states on 13th February 1781, half of those since the start of the 20th century. Each time the Wall Street adage has proved correct “The good news is the world can only end once and this ain’t it”. Warren Buffett probably has it right when he says, “Never bet against America”.

Putting all this together; China prepared to prime the pump again, easing supply chains, the most promising signs yet that Covid can be controlled, and an indication that the Fed may yet control inflation without causing a recession, provides a platform for the global economy to perhaps perform much better than most assume over the rest of this year and into 2023.

The cause of the downturn in global equity markets is obvious – the upsurge in inflation and the consequent need to raise interest rates and risk a recession. A combination of surging inflation and looming recession reminds me of the quote from soccer manager Tommy Docherty, ‘When one door closes, another one slams in your face’.

If a recession ensues but inflation persists, we will not have seen conditions of this sort since the 1970s when the term ‘stagflation’ was coined. In 1974 inflation in the UK, as measured by the CPI, was 24.24%. In an example of history not repeating itself but rhyming, as Mark Twain observed, the 1970s inflation was boosted by the Arab oil embargo which followed the Yom Kippur War. On this occasion, we have a similar effect from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

For global equities, 2022 has been the worst start to a year this century. As of the end of June the MSCI World Index, a basket of large and mid-cap stocks across 23 developed markets is down 18%- worse than the routs at the same point in 2002, 2020 and even 2008. The return on government and corporate bonds and other assets has been no better and, in some cases, much worse.

US stock market indices are well into bear market territory (defined as falls of more than 20%). Some stocks, Netflix, Klarna, Twitter, to name but a few, are down 50%+ and Bitcoin is down more than 60%. But the 20% + drawdown is still far from the 30-35 per cent crashes that have typified past bear markets and many worry it is only the beginning. That bearish consensus, combined with very high uncertainty makes markets feel perilous.

We recognise that this is an uncomfortable time for even the most experienced investor but times like this are when it pays to stay level-headed. While recession remains a possibility, the economy is undergoing historic shocks and unpredictable effects – and markets are along for the ride. If inflation abates, so could recession fears, bolstering the case for buying the recovery.

Excluding the current situation, the S&P 500 has weathered six bear markets over the last five decades. Investors can learn a few important lessons by examining those downturns.

The first lesson is that each bear market differs dramatically in terms of duration and severity. It took more than one year for the S&P 500 to reach bottom during the great financial crisis-induced recession, but it took just over one month for the market to bottom out at the onset of the Covid 19 pandemic.

The second lesson requires investors to read between the lines. Losses sustained during a bear market are eventually washed away by the next bull market. After every downturn, the S&P 500 has recovered and gone on to hit new highs. In fact, over the last five decades, the average bear market saw the S&P 500 fall 41%, but the average bull market saw the index rise 259%.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to accurately predict market cycles. No one knows when the current bear market will end. That means trying to time the market is essentially gambling. If you take that approach, there is a good chance you will eventually get burned, and the impact could be catastrophic for your portfolio.

Consider this cautionary anecdote: The S&P 500 climbed 517% between January 2002 and December 2021. But if the 10 best days are excluded – just 10 days in two decades – the total return would have been just 183%. And guess what? All the 10 best days occurred during bear markets, and six of them took place before the bear market had reached a bottom.

In the end stock markets go up and stock markets go down – it is their nature – but good quality companies have an innate ability to survive economic turmoil. In this market, even short-term air pockets in earnings growth are punished with great ferocity as investors pivot to short-term profit harvesters, like oil, gas & commodities.

This macro-driven market will be highly volatile and prone to periods of unbelievable overshoot at times. Many fantastic businesses are being unfairly chucked aside by short-term fears. Meanwhile, there are some helpful market and economic signals emerging. A lot of bad news is baked in so the potential for more negative surprises has markedly reduced. Plus, the guiding principle of a five-year investment horizon smooths a lot of cracks on precise timing and trajectory.

From that perspective, now could be a great time to invest in the stock market.

As always, we thank you for your continued support and we look forward to updating you regularly throughout 2022. We invite you to get in touch if you have any questions.

Keith W Thompson

Clarion Group Chairman

July 2022

Creating better lives now and in the future for our clients, their families and those who are important to them.

The content of this article does not constitute financial advice and you may wish to seek professional advice based on your individual circumstances before making any financial decisions.

Any investment performance figures referred to relate to past performance which is not a reliable indicator of future results and should not be the sole factor of consideration when selecting a product or strategy. The value of investments, and the income arising from them, can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Unless indicated otherwise, performance figures are stated in British Pounds. Where performance figures are stated in other currencies, changes in exchange rates may also cause an investment to fluctuate in value.

If you’d like more information about this article, or any other aspect of our true lifelong financial planning, we’d be happy to hear from you. Please call +44 (0)1625 466 360 or email [email protected].

Click here to sign-up to The Clarion for regular updates.