Category: Business

| “Both optimists and pessimists contribute to society. The optimist invents the aeroplane, the pessimist the parachute.” George Bernard Shaw |

“Summer days are over; summer work is done. Harvests have been gathered, gaily, one by one”.

With the dark nights of winter fast approaching, here is a short review of the main economic developments over the last few months.

The world economy has continued, by and large, to do slightly better than expected, with economists nudging up their forecasts for growth this year in the US, Japan, and the UK. Inflation is falling and has been coming in below market expectations for the first time in some time. It is not, however, all rosy.

Europe’s growth is weak, China’s recovery has stalled, and oil prices have risen by almost 20% in the last three months. The timeliest measure of economic activity, the purchasing managers’ surveys, suggests that after a second-quarter bounce, activity in the US and Europe has flagged in the last few months.

Labour markets in the US and Europe remain tight but, in a sign that higher interest rates are working, unemployment numbers have edged higher, and vacancies have fallen.

The US remains the growth outlier among rich economies. Its economy, while slowing, continues to show decent growth and inflation has dipped more sharply than in Europe to 3.7%. Manufacturing activity has softened but consumer spending, the principal driver of growth, has remained solid over the summer. The US Federal Reserve has said that it no longer expects the US to fall into recession.

European growth has been weaker over the last year than in the US but the latest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data shows UK and Euro area growth improving in the second quarter. Germany and Sweden have seen their economies shrink over the last year. Spain, Ireland, and Portugal have overperformed.

UK GDP growth may be lacklustre, but wages have rocketed, with regular pay excluding bonuses rising by 7.8% in the last year, the fastest rate since records began 22 years ago.

Higher interest rates have helped to slow but have not crushed inflation and over the summer the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Bank of England (BoE) raised rates again. Markets think that the Fed and the ECB have probably finished raising rates but, after a September pause, anticipate a further 25bp rate increase from the BoE.

While financial markets think that interest rates are at or near their peak, they do not expect a return to the very low rates seen before the pandemic. This can be seen in the bond market where yields on US ten-year government bonds have reached 4.8%, a level not seen since 2008.

This roughly corresponds to an expectation of short-term interest rates averaging 4.0% over the next ten years, compared with an average rate of 1.2% in the last ten years.

Other news was the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) revised GDP estimates for 2020 resulting in an upward revision for the Covid period with growth 0.6% higher than previously thought. Recorded output in 2021 was also higher than previous estimates at 8.7% growth.

Overall, GDP in the fourth quarter of 2021 exceeded pre-Covid levels and real output in the last quarter was 1.6% above the fourth quarter of 2019 level, rather than the previous estimate of 0.2% below.

What is the significance of these revisions? It means little in terms on inflation and interest rates, but it shows the UK in a more favourable light. For the time being, it is Germany that is in bottom place within the G7. More generally, it demonstrates that GDP figures are broad gauges of activity and are subject to revision – although the magnitude of these changes is unusual.

Concerns about China’s economic performance have grown over the summer. A hoped-for post-COVID boom has failed to materialise and, far from suffering the inflationary excesses of the West, price pressures have receded rapidly.

Inflation has turned negative over the last year stoking fears of deflation. The authorities have sought to bolster the economy by cutting interest and mortgage rates and by stepping up support for the renminbi, which has fallen by more than 5.0% against the dollar this year.

While Chinese recovery has stuttered, Japan’s has moved up a gear over the summer. The Japanese economy grew by a remarkable 1.5% between the first and second quarters, far faster than any other major industrialised country including China.

Over the summer, a certain familiar fairy tale kept cropping up in financial markets: Goldilocks. Key economic data releases were neither too hot nor too cold, but just right, like the porridge sampled in the story by the plucky young eponymous hero.

Jobs and inflation figures were bright enough to suggest the US economy was withstanding the Federal Reserve’s scorching campaign of interest rate rises, and dull enough to suggest the central bank might not need to do too much more to get inflation back in its box.

The question is whether the boost to growth that comes from falling inflation will offset the dampening impact of a weaker jobs market and high interest rates. It’s a hard call and after a spring bounce, activity in Europe and the US is likely to ease in the second half of the year but stay positive enough to avoid recession.

Emerging Markets

Humans have an innate desire to sort and categorise the world around them. The economist Antoine van Agtmael is no exception. In 1981 at the World Bank, he coined the phrase “emerging markets” as a more aspirational alternative to the term “third world”.

The label has since become synonymous with a hotchpotch of fast-growing nations considered to be riskier investments than “developed markets”.

But while it may have been a successful rebrand, for economists and investors the catch-all term has become unhelpful and even misleading. In investing terms, a country only really grows up once it becomes a developed market.

Being an “emerging market” is a bit like being a teenager. You are on the edge of being taken seriously by adults – but not quite!

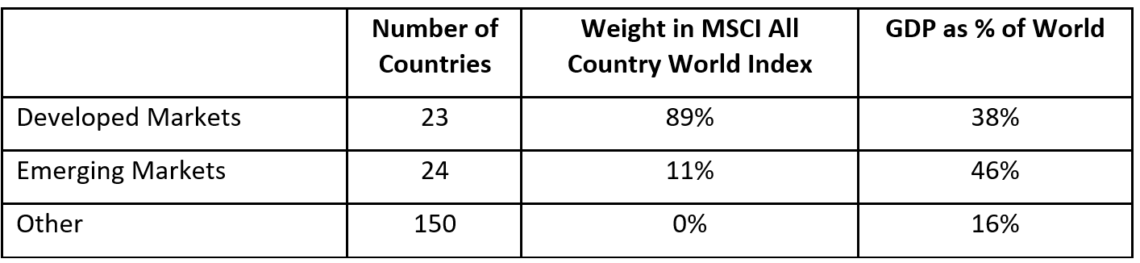

In terms of GDP, in 2011, Emerging Markets became bigger than Developed Markets for the first time. And today, Emerging Markets represent 46% of world GDP, while Developed Markets account for just 38%.

And yet, Emerging Markets represent just 11% of the MSCI All World Index. And another 150 countries don’t feature at all.

Source: MSCI/UN/7IM/IMF

For one country, being treated like a kid is starting to get really annoying.

South Korea was classified as an Emerging Market by MSCI in 1992 – fair enough, given a GDP per capita (wealth per person) basically half that of Spain.

Now though, South Korea’s GDP per capita is 15% higher than Spain’s (and about the same as the UK). It has more global companies than Hong Kong and a higher life expectancy than New Zealand.

S&P recognised South Korea as Developed in 2001. FTSE did the same in 2009. And yet in its annual review of markets in July, MSCI announced that South Korea is still ‘Emerging’.

South Korea is getting frustrated. It can drive. It can drink. It can marry. But it’s still not allowed to sit at the adults’ table!

It’s another good reminder of the power that index providers hold and all quite confusing for someone who invests in a World All Country Index Tracker!

Emerging markets that account for most of the world’s population are not homogeneous. Rather they consist of dynamic and highly diverse countries at different stages of development and their composition has changed vastly since the term became popular.

A key determinant of future returns is the extent to which the price paid represents good value. Other factors contribute, including the performance of the underlying universe from which the investment has been chosen, whether the fund managers achieve outperformance relative to the indices, and the length of time invested to best compound returns and ride out short-term volatility. But the price paid remains of key importance and currently emerging markets appear very good value relative to their growth prospects.

Figures suggest that since 2012, emerging markets have underperformed developed markets by as much as 60%. The US market now trades on cyclically adjusted price earnings multiple of around 24, while emerging markets trade on 11, a 25-year low. In fact, by many measures, the emerging market index is now at its lowest since being introduced. Yet the outlook for growth when compared with developed economies remains encouraging.

Company returns over the past decade have broadly matched those of developed markets but share prices have been savaged, having de-rated from a comparable price/book value to now barely half of that.

Indeed, while there will always be exceptions, emerging market companies in general are less dependent on debt, have improved corporate governance, and boast competent managements which are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of good shareholder relations.

It is widely predicted that economic growth in emerging markets will exceed that of developed economies. And much of this growth is from growing cities.

According to consultancy firm McKinsey, an estimated 440 emerging market cities are expected to have contributed around half of global GDP growth between 2010 and 2025. Rising prosperity is resulting in increasingly wealthy populations, rapid urbanisation, and huge investments in physical infrastructure.

Recent shocks have also underscored the economic diversity across emerging markets. On the policy front, central banks were particularly aggressive in raising interest rates to get ahead of inflation in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

While inflation will remain ‘stickier’ and more volatile than the consensus forecast suggests, these central banks will have greater latitude in cutting rates as inflation falls. This could be a short-term catalyst for markets to re-rate and power ahead.

The interest rate outlook took an interesting twist when the BoE’s Chief Economist Huw Pill used a mountain analogy to show different potential paths for monetary policy.

Speaking in South Africa he referenced the characteristics of the Matterhorn and Table Mountain and said that there were different ways to fight inflation via interest rates.

He said: “Some of them have rates rising rapidly and falling rapidly in what is known as the Matterhorn profile. The alternative would be to hold restriction for longer in a more steady and resolute way with a profile for interest rates that looks more like Table Mountain.”

Investors took his preference for the latter to mean that he favoured a lower peak but a more sustained period of higher rates. And, indeed, this profile has been factored into market pricing with rates in the 5 – 5.5% area through 2024. Pill re-iterated the commitment to get inflation back to 2%, but markets remain more sceptical with implied inflation, looking at conventional and index-linked yields, above 3% at longer maturities.

JK Galbraith, the renowned Canadian American economist once said that the only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.

Although well-known this prescient insight is usually ignored and undue importance is attributed to forecasts by various economic financial and government organisations, even though a cursory glance at their track record, usually leaves little doubt as to their worth.

The lessons of the past year or so should be sobering. The International Monetary Fund led the way last year in forecasting a deep economic recession. As recently as spring their strategists were more bearish than at any time since the financial crisis of 2008/2009.

Yet now the organisation has turned on a sixpence and raised its global growth forecast to 3% for next year. Talk of recession has vanished into thin air as though it never happened. Indeed 25 of the IMF’s past 28 UK growth forecasts have been too low. Until only recently, it was forecasting that the UK would be one of the few European countries to fall into recession, and yet recent data has been quite the opposite.

The folly is also evident at home. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has had to significantly reduce its forecasts for public sector net borrowing on several occasions. Recently net borrowing turned out to be a huge £100 billion below the OBR’s forecast.

Little wonder then that a recent annual assessment of 30 economic forecasts compiled by David Smith of the Sunday Times showed the OBR came third from the bottom.

This brings us to the woeful record of the BoE, whose popularity among the public is now at an all-time low. In autumn of last year, it predicted a harsh and protracted recession with a 3% fall in gross domestic product. Its record on inflation is no better having been long behind the curve.

The defence that it cannot be expected to account for external shocks simply does not hold true given the period before Russian’s invasion of Ukraine, the biggest ‘shock’ of all saw inflation rising steeply and reaching 6.1% and yet interest rates were still at 0.5%, woefully below what was needed to achieve its objective of 2% inflation.

Whisper it gently amid the noise but reality is yet again proving the consensus forecasts wrong. Economies have not slipped into recession. Budget deficits and finances are better than expected. Company results have not plunged into the abyss.

Corporate finances are in decent shape and defaults remain low because companies have tightened their belts by reducing their costs and borrowing. This protected margins and profits.

Yet, largely because of the “importance” of those making these forecasts, this folly is accepted and has conditioned stock markets to bad news. With money supply growth now negative and budget deficits retreating, the impact of higher interest rates as evidenced by lead indicators such as the housing market faltering, suggests the peak is near which could well be a catalyst for markets to move higher.

In short, there will always be risks in investment. But as it becomes increasingly evident that the risks are falling away, now is a good time to invest. Do not wait for the forecasters to suggest it is because by then it will be too late.

As ever, it will always be prudent to retain some firepower via more defensive assets given that volatility will be the usual travelling companion on such a journey. However, while timing is important, it is usually better to be too early than too late. Markets can move rapidly when sentiment shifts.

As always, we thank you for your continued support and we look forward to updating you regularly throughout 2023. Please get in touch if you have any questions.

Keith W Thompson

Clarion Group Chairman

September 2023

Creating better lives now and in the future for our clients, their families and those who are important to them.

Any investment performance figures referred to relate to past performance which is not a reliable indicator of future results and should not be the sole factor of consideration when selecting a product or strategy. The value of investments, and the income arising from them, can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Unless indicated otherwise, performance figures are stated in British Pounds. Where performance figures are stated in other currencies, changes in exchange rates may also cause an investment to fluctuate in value.

The content of this article does not constitute financial advice and you may wish to seek professional advice based on your individual circumstances before making any financial decisions.

If you’d like more information about this article, or any other aspect of our true lifelong financial planning, we’d be happy to hear from you. Please call +44 (0)1625 466 360 or email enquiries@clarionwealth.co.uk.

Click here to sign-up to The Clarion for regular updates.